Her name is Wangui. Her mother’s sister once told her that, a woman’s worth extends only as far as the success of her children. The only success that counts is of a narrow, claustrophobic definition. If the children are sons, the expectations rise a notch. Daniel, her only child, is 8 months old now.

Water drips from the shirt she is hanging on the clothes line and the drops fall onto her slipper-shod feet. “Sasa mama Dani!” a neighbour calls out from a window overhanging the drying yard. ”Poa, mama Alex.” Wangui can’t stand that word ‘poa’. What kind of response is that anyway? Answering in any other way would offend the neighbour and be considered haughty. Wangui has had 2 years to learn.

Thirty windows overlook the yard in that corner of Kayole estate, where space is a fantasy. Landlords deem it a waste to make provision for parking space, clothes drying yards, or even paths between the blocks of flats. When they do, they are sure to allocate no more than a few square inches for each. Wangui grew up in Murang’a where she could run through vast open spaces and run down hills with the wind in her hair and threadbare dress. Kayole is stinky and stifling in contrast.

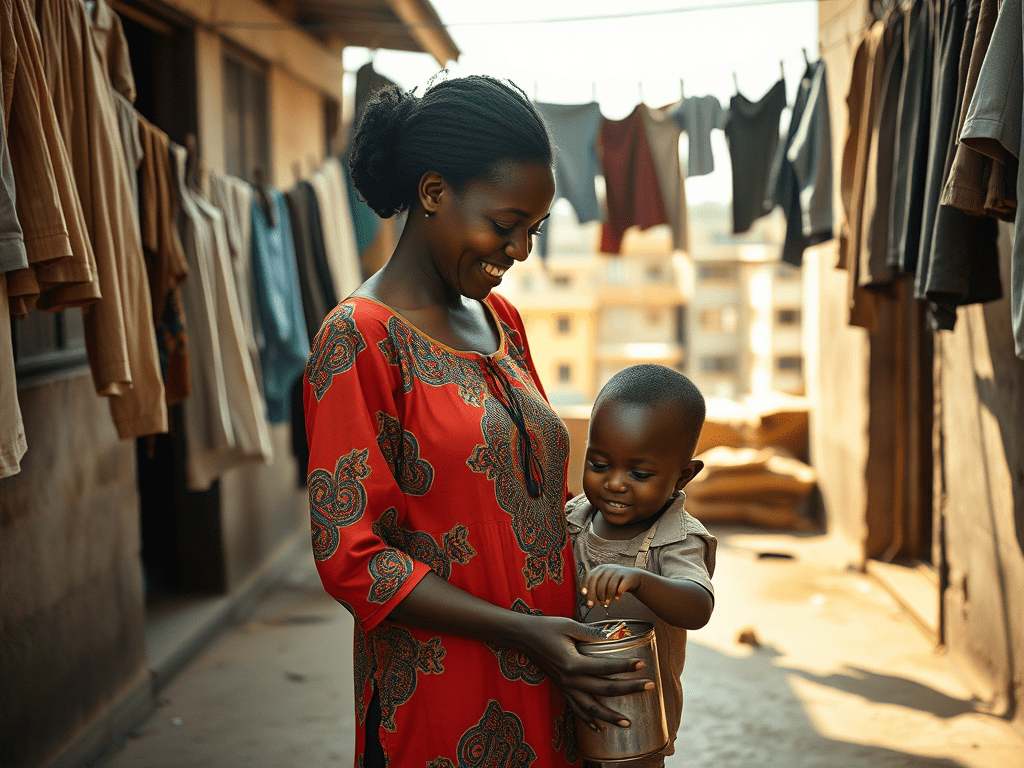

Daniel giggles at each rattle of the pegs in the Kimbo tin he is shaking in his tiny hands. The giggles erupt into childish rapture when some of the pegs fall out. Wangui looks down at him and smiles. He returns her glance with one of his winning two-teeth smiles then gets up, stumbles towards her awkwardly and hugs her knee. She puts the last peg in place and, still smiling, gathers son, clothes’ pegs, tin and bucket.

As she walks back to the house, she passes a group of teens talking in low tones. The sound of her footsteps on the concrete is greeted by a nervous silence. They turn to stare at her. She knows they are waiting for her to pass out of earshot. She shudders to think what they could be discussing. She has heard stories…

In the house, the monotony of the tasks before her is a dead weight that threatens to break her back. She decides to start by clearing the bedroom. The mess is unbelievable. Ken, her husband of two years, and Daniel seem to revel in clutter. Between the two of them, they have managed to turn the room into a dump only days after she had cleaned it out. Wangui sighs.

Her thoughts are making a bee-line in her mind, each grappling for priority. She refuses to give way to them. She knows they will overwhelm her and re-engrave the worry lines on her face. Engrave. That’s what they did to the cross that now stands over her brother’s grave. They engraved the name and the dates, as if his life could be reduced to a few careless scars on cheap wood. She wonders whether her niece will get over her father’s death. Will his former employers settle the hospital bill and funeral costs? How much will she need to chip in? The thoughts have burst through and there’s no stopping them now.

They need money and badly. Perhaps its time to let go of her pride and send a text message to 2929. Or was it 6969? Or both? There are so many get-cash-quick options on hand, so many ways to win the lottery and twice as many ways to lose bits of money chasing delusion. But if she had a million shillings…they could settle all of theirs and her brothers loans…buy a gas cooker to replace the kerosene stove…perhaps move to a better neighbourhood.

As the next thought takes over, she looks over to where her Dani is playing. This time he is standing on the bed clutching onto the window sill, mumbling to himself and doing a baby dance. This is not where she would like to raise him. She has big dreams for this boy, nothing like the stories she has heard about the neighbourhood kids. Brian from block C is an alcoholic and they sometimes have to go and bail out of police cells after he’s been collected, unconscious, by the side of the road. He’s 15. Where they live, the police don’t care that he’s a minor, just that he’s drunk and disorderly. Njoro who lives two floors below Wangui is in remand. Police say he was in a gang that was caught robbing violently, wielding knives. He says he just had the wrong friends and was with them at the wrong time. He’s 18 and a high-school drop-out. The neighbourhood stories like this are relentless. Their mothers must have had big dreams for them too. They must have seen them the way she sees her toddler, the start of something great. So what will happen to hers?

By this time, Dani has found playmates from across the block. The blocks of flats are so close together that opposite windows have only about a metre of space between them. The window is half open and being on the fourth floor, it has no grills. Mama John’s two children are rarely let out of the house so it’s exciting for them to play with a neighbour. Daniel’s vocabulary is only a couple dozen words more than ‘eeeeh’ and ‘wawa’ but for kids, that’s more than enough to converse. In any case, the two others are two and four so they make the bigger contribution.

Wangui is on the other side of the room trying to sift through a pile of magazines and old newspapers. She is not interested in the child talk going on behind her.

Suddenly, something said behind her makes her stop and freeze. It takes a moment for her to react. ” Toto, kuja.” Come. She turns and Dani is doing exactly that. He is on all fours on the window sill and his head is already out of the window, tiny body squeezing through the space between the large metal grills. Her heart races to the beat of four-floors-down that is now ringing in her mind. She can see her dreams for Daniel shattering on the ground below and spewing with his split skull and emptied brains…

She leaps. The tiny foot is caught in her hand just before it slips off the edge. She squeezes hard. He screams; half in fright, half with the pain of the grip. She draws him to herself and holds him there.

© 2023 Wambui Wairua. All rights reserved.